News + Blog

Medical Illustrators & the Fight Against COVID-19.

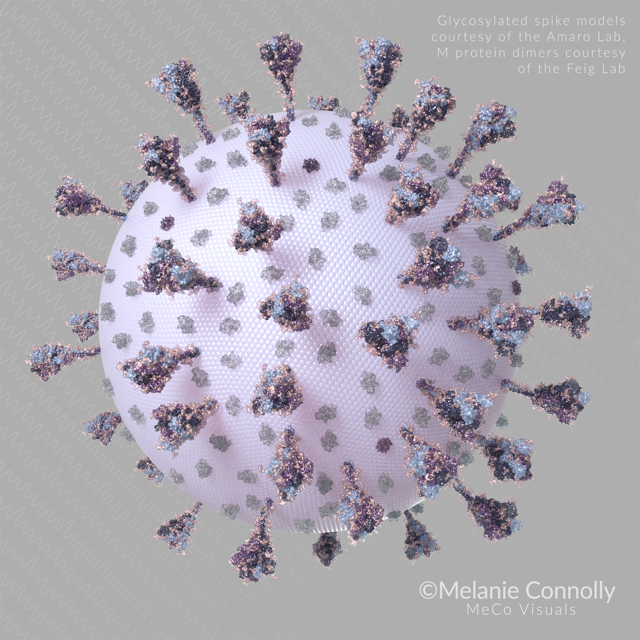

How do you fight something you can’t see? Thanks to medical illustrators like Melanie Connolly of Chicago Medical Graphics, we are able to put a face to the name of COVID-19.

We sat down with Melanie and picked her brain about her work as a medical illustrator and the responsibility that the vocation carries in the time of a pandemic.

ARS: Tell us a bit about what medical illustrators do. What does this mean during a pandemic?

MC: We break down the science. When the public is on high alert and research is updating daily, you have a kind of perfect storm for the spread of misinformation. People are going to naturally crave and seek out more information about the virus, but a lot of it will be wrong. Knowing that the information they are looking at came from a trusted source is especially important right now. We speak the language of the researchers, and we help focus their complex work into something digestible for the public that has a clear take-home message. When we’re talking about a viral particle that is generally unseen, it can be difficult at first for people to understand the damage that something so small can cause. We work at all scales, from atoms and proteins to ecosystems, to show how such a tiny particle can have such a massive effect, and to show how one person’s actions can affect so many, especially now.

ARS: Is there a typical process you follow when creating a rendering, or does it vary by project? For example, what was the process in creating the SARS-CoV-2 rendering?

MC: It definitely varies. With this piece, I was very lucky that several medical illustrators had begun putting their heads together to disseminate research. Michael Konomos of Emory, David Goodsell of the PDB, Jennifer Fairman of Fairman Studios, Dave Ehlert of Cognition Studio, Veronica Falconieri of Falconieri Visuals, and several others had begun to build a body of research. I love studying viruses, but with the amount of constantly-changing information my head was spinning the first day. I was able to learn from their research and add to it where I could. I wanted to build a version of the virus with several “open” conformation spikes that were ready to bind. We’re still trying to disseminate the exact mechanism as to how the spikes bind ACE-2 on human alveolar lung cells. For this piece, I imported the individual parts of the virus into Zbrush and then 3DsMax, and spread the molecules around a sphere based on how many of each are likely on the virion. In this case, we have several closed and a few open large trimer S spikes, numerous M surface proteins (PDB 3I6G), and a few E pores (PDB 5X29). About a week after I built this piece new research came out regarding glycosylation of the S spikes- so I need to do an update already!

ARS: When composing these renderings you must, at times, feel a tug-of-war, between creativity and scientific accuracy.. Has there been an instance where you felt as though the importance of one outweighed the other?

MC: Whenever you are simplifying something, the story often becomes slightly less true. I teach piano, and I think of it as learning an easier version of a Beethoven piece when you are a new student- it may be in the same key, but many notes are missing and several are moved around. The heart of the music is there, and the easier piece is a stepping stone geared to your level of ability. The goal is to bridge steps in the audience’s understanding so that they can eventually get to the next level. So it depends on the audience, and the message we want them to take home. We always want to be as scientifically accurate as possible, but sometimes the story is better assimilated through artwork that is simpler. There’s also the fact that we love beauty and marvel at creativity. If you can get someone to look at your artwork for a few seconds more because it is really strikingly pretty, they might learn just a little bit more. There’s definitely a sweet spot to hit, and it changes for the needs of each piece.

ARS: The work does not stop at just identifying the virus. How are you and other medical illustrators visualizing finding a cure?

By diving into the structure of the virus, how it replicates, binds, travels on droplets or throughout the body, we can look for weak spots that could be exploited. Researchers are making amazing strides in an unbelievably short time, and our job is to show people the mechanism that is being focused on, so that they can understand it. As much as we may not agree with it, many people are afraid of treatments or vaccines. By clearing up the science surrounding the mechanism of action, we can help assuage fear and ideally get more folks to participate in the absolutely necessary herd immunity that immunocompromised individuals will rely on once a vaccine is available. This will be crucial.

ARS: Medical illustrators are like the unsung heroes of the medical world. What is one thing you would want the world to know about your profession?

MC: We exist! I know so many folks who went into medicine and had an art side, or went into fine art and miss science. We’re here, and there are so many ways to become a medical illustrator. We also do SO many different things- we call it illustration but it was never just that. We make educational games (that are actually fun) and work in extended reality. Many of us make prosthetic eyes, ears, noses and fingers. I personally make predominantly medical animation, but the field runs from carbon dust and pen and ink to interactivity and 3D printing. As a medical illustrator, you definitely learn how to be a jack of all trades, and that often even includes managing a business! I like to tell clinicians that if they have a discussion with patients several times where they are using their hands a lot but the point often doesn’t seem to get across, that’s where I can help. We decipher, research, and then we get to build! Someone once asked me “hasn’t everything about the human body already been drawn?” and I will fully admit I laughed. Take this virus for example- our understanding of it is rapidly changing. Veronica Falconieri and I were chatting the other day, and she pointed out that part of doing our job means accepting that some of what we create may be proved incorrect at some point. We are an endlessly curious group and we dive into the research, but medicine changes, and anymore it’s changing rapidly. If anything, it’s a testament to the fact that we are even more needed than before- people need tools to quickly understand the biological complexities of what is going on in order to make informed decisions fast, and we are trained specifically to create those tools.